We all know that history is written by the victors. Nobody is sure which white man first said that, but it really doesn’t matter as the patriarchy has made sure its heroes have been prominently memorialized in the pages of newspapers and history books and on the walls of museums.

In the early 1990s, along with my VU Production partners, I was trying to convince TV network executives to produce a series on women’s contributions to the 20th century. We were turned down by all three — and there were only three networks at that time. Then someone suggested that I take the proposal to an unlikely television executive — Ted Turner. He had launched CNN, transformed the cable business and was married to Jane Fonda, but was not the first man I thought of for the project. But he asked exactly the right question: “Is this history in the history books?"

"Not much of it," I replied — and that, regrettably, is still true.

That’s all it took to convince Ted to greenlight the six-hour series, A Century of Women — women’s history from 1900-1992. We produced the series which was broadcast on TBS in 1994 and in many countries around the world. It became the first television series to be selected for the Schlesinger Library of Women's History video archive where it is easily accessed for research purposes by Harvard and Radcliffe students. But a lot has happened since 1994, and we are already nearly 20 years into the 21st century!

Throughout my media career, finding ways to engage the power of media to raise awareness of women's stories, accomplishments and challenges has been a central theme of my work, believing, as I do, that " we can’t be what we can’t see" and we can’t remember what was never recorded.

This truth was revealed earlier this month when The New York Times published its “Overlooked” project. The idea was hatched after Amisha Padnani was hired as a digital editor at the obit desk and quickly realized in the course of her work that the obituary pages had long been dominated by men, especially white ones, since the paper’s inception in 1851.

Even in the 21st century, that dominance hasn’t abated. In the past two years, the ratio of obituaries about men and women was still 5 to 1. So, Padnani and Jessica Bennet, the Times first gender editor, spearheaded a project to write obituaries for women who had “left indelible marks but were nonetheless overlooked.”

Among the “15 remarkable women” in the inaugural collection are Ida B. Wells, Charlotte Bronte, Henrietta Lacks, Sylvia Plath and Marsha P. Johnson. Many were shocked that the deaths of the authors of enduring works like Jane Eyre and The Bell Jar passed unremarked by the editors of the Times.

AWHM Congressional Commission members, from left, Mary Boies, Marilyn Musgrave, Kathy Wills Wright, Maria Socorro Pesqueira, Emily Rafferty, Bridget Bush, Jane Abraham and Pat Mitchell (Photo by Vincent Ricardel)

The oversight is multiplied when you consider that there is no physical museum dedicated to the history of women in this country in our nation's capital. We have museums chronicling the history of everything from stamps to space to spies, and gratefully there is a virtual women’s history museum (NWHM.org) which has offered online exhibits celebrating women’s history for many years. The NWHM team has also created curriculum to respond to the need for more women’s history in America's classrooms. Curriculum that their recently released research, Where are the Women?: A Report on the Status of Women in the United States Social Studies Standards, examining the status of women's history in state level social studies standards indicates is badly needed.

NWHM has also advocated for a physical museum in the nation’s capital and supported the creation of a congressional commission to advance the idea. Last year, that idea was moved forward by the appointment of a bipartisan congressional commission to study the feasibility of building a national museum of women’s history. Leader Nancy Pelosi appointed me to the commission which included the distinguished group of women in the photo (right). After 18 months of exploration and research, we presented our findings and recommendations to Congress that an American Women’s History Museum is indeed feasible and necessary.

Progress, yes, and last week, the Smithsonian announced a new women's initiative that charts a path forward to showcasing women in all the Smithsonian museums with special exhibits and women’s curators, and the goal, hopefully, of building a physical museum in Washington, DC, adding women's stories to the historically important museums documenting the history of Native Americans and African Americans. The women's initiative will officially launch in 2020 with exhibits celebrating the passage of the 19th Amendment.

( l-r) Artist Jann Haworth, Diane Stewart, Pat Mitchell and Susan Cofer at Diane's gallery in Salt Lake City to view an exhibit by Jann about the Women's March.

During this year’s Women’s History Month, I also wanted to share a personal story of another historical oversight with current relevance: artist Jann Haworth, who was erased from history herself, and now is devoting her art to ensuring other women in history are not forgotten. Jann was one of the co-creators of the iconic Beatles’ album cover, "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band," which turned 50 last year, and her collaborator and husband at the time, pop artist Peter Blake, is the one more remembered and celebrated for the cover.

“Looking back, I’m horrified that of 71 famous faces, the Beatles chose no women,” Haworth told the London Express last year. “Peter and I added only 12 women and three of those were Shirley Temple. The rest were pin-ups, mannequins or blondes such as Mae West and Diana Dors. If we made the cover today we would never have allowed such inequality."

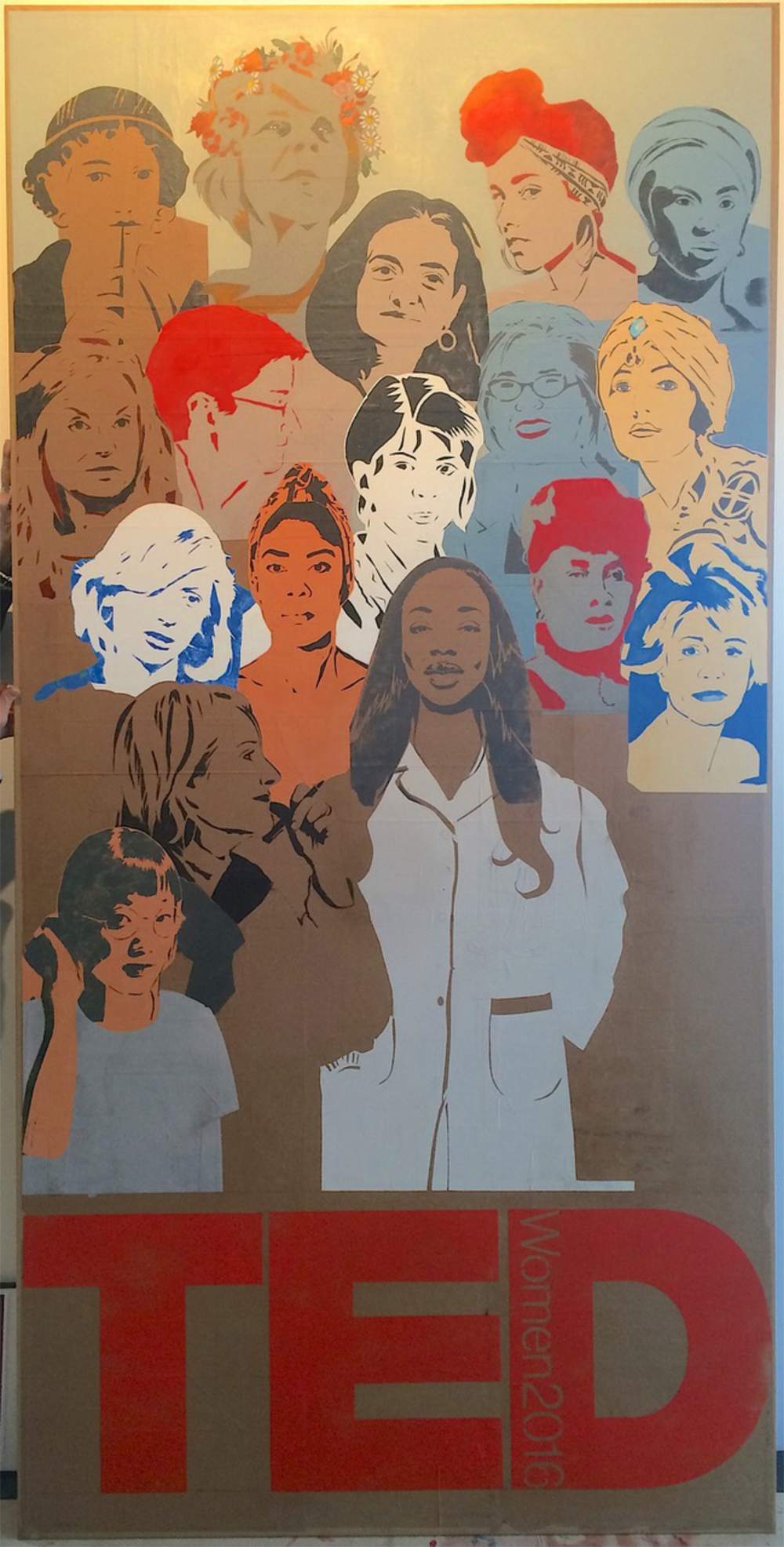

"Work in Progress" mural. (click to enlarge)

Haworth, 75, now lives in Sundance, Utah, where we first met and I first saw her “Work in Progress” mural — a collaboration with her daughter, artist Liberty Blake, and photographer Lynn Blodgett — that presents in a series of panels, an artistic interpretation of more than 250 women who helped shape the world through contributions in the arts, sciences and social justice activism.

A panel created at TEDWomen 2016.

Haworth tells me that she was inspired to create the mural after doing a comic strip in 2009. “It was called ‘Mannequin Defectors’ and in the last panel the mannequins were marching past a piece of street art that was a mural of notable women. I needed about 25 to 30 heads. I wanted women from all areas, not just the arts, not just American, not just white, etc. etc. and — I had a moment! I realized I didn't know MY history. That's when I thought, 'This should be an interactive art project to engage other women and men in discovering women's stories.'”

The mural is collaborative art in that people are invited to attend workshops where they choose a woman in history and with stencils and art materials, they create portraits which Liberty later incorporates into the larger mural. After seeing the process at the Salt Lake Art Museum, I invited Jann and Liberty to TEDWomen in San Francisco in 2016, and there, TEDWomen attendees selected women from TED’s history and created a new panel for the mural. Again in New Orleans in 2017, TEDWomen attendees eagerly contributed to the mural with more portraits. Over the past two-plus years, the mural has grown to nine panels measuring 56 feet showcasing over 250 portraits made by 200+ community members. Two new panels that will be collaged and added in April.

The mural is always growing. As Haworth says, “Complete? Never! That’s one of the two reasons it’s called ‘Work in Progress.’ The other is that it’s about progress.” As Haworth and Blake take the work to different cities, they hold workshops in which local community members are encouraged to nominate women for inclusion or choose from a list and create their own stencils as part of the project.

When I asked Haworth which were her favorite representations, she reeled off a list. “Bessie Smith, because of the woman who cut her image. Mata Hari, I read everything I could find about her and was deeply saddened by her tragedy. Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Mother Jones. Victoria Woodhull. Angelica Dass. Eve Ensler... Actually, this list doesn't stop.”

Haworth says the workshops have been wonderful engines for discovery, with “young women discovering things and older women realizing how much they didn’t know. The format of the workshops is like a sewing circle. We've learned a lot about how when you are engaged in art making and the creative process — the stories come out.”

Since premiering in 2016 at Utah MOCA, the mural has traveled to nearly 20 venues, including Washington, DC (for the first Women’s March and on Capitol Hill for the as part of the Commission's report to Congress proposing an American Women's History Museum), and it's been seen in galleries in Vienna and Paris and, this month, New York City. Appropriately, Jann’s mural with its selected women from the past, will be exhibited at XXHouse, a project of two young women who, like Jann (and other artists, writers, composers, scientists, engineers and activists), are committed to celebrating women’s history as well as making it.

"A person with no stories has no history nor future,“ was one of my grandmother’s favorite sayings, and I believe it. That’s why I’m committed to getting women’s stories front and center at every opportunity, to promoting and advocating for women’s stories on television, in film, on the TEDWomen stage, and ultimately for a national women’s museum. We can’t all write a movie or play or create art but we can share our own stories and tell the stories of other women so that no woman’s story gets unreported or her death go unrecorded or her accomplishments assigned to someone else.

I challenge us all to discover a woman’s story we did not know and to celebrate her story by sharing it with others.

— Pat