Today marks the 30th anniversary of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), landmark legislation that brought family violence out of the shadows with increased law enforcement and community support for survivors of domestic and sexual abuse.

The law exists because of President Joe Biden, who co-wrote and championed the bill, along with NY Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, Senator Barbara Boxer and others. It was finally signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

As former US Senator Barbara Boxer told CNN this week, “[Then Senator Biden] made it happen, and he took it out of the shadows. In those years, violence against women, especially in marriages and relationships, was the best kept secret. A woman would show up with a bruise on her face. She would never say her husband did it. It was hardly considered a crime.”

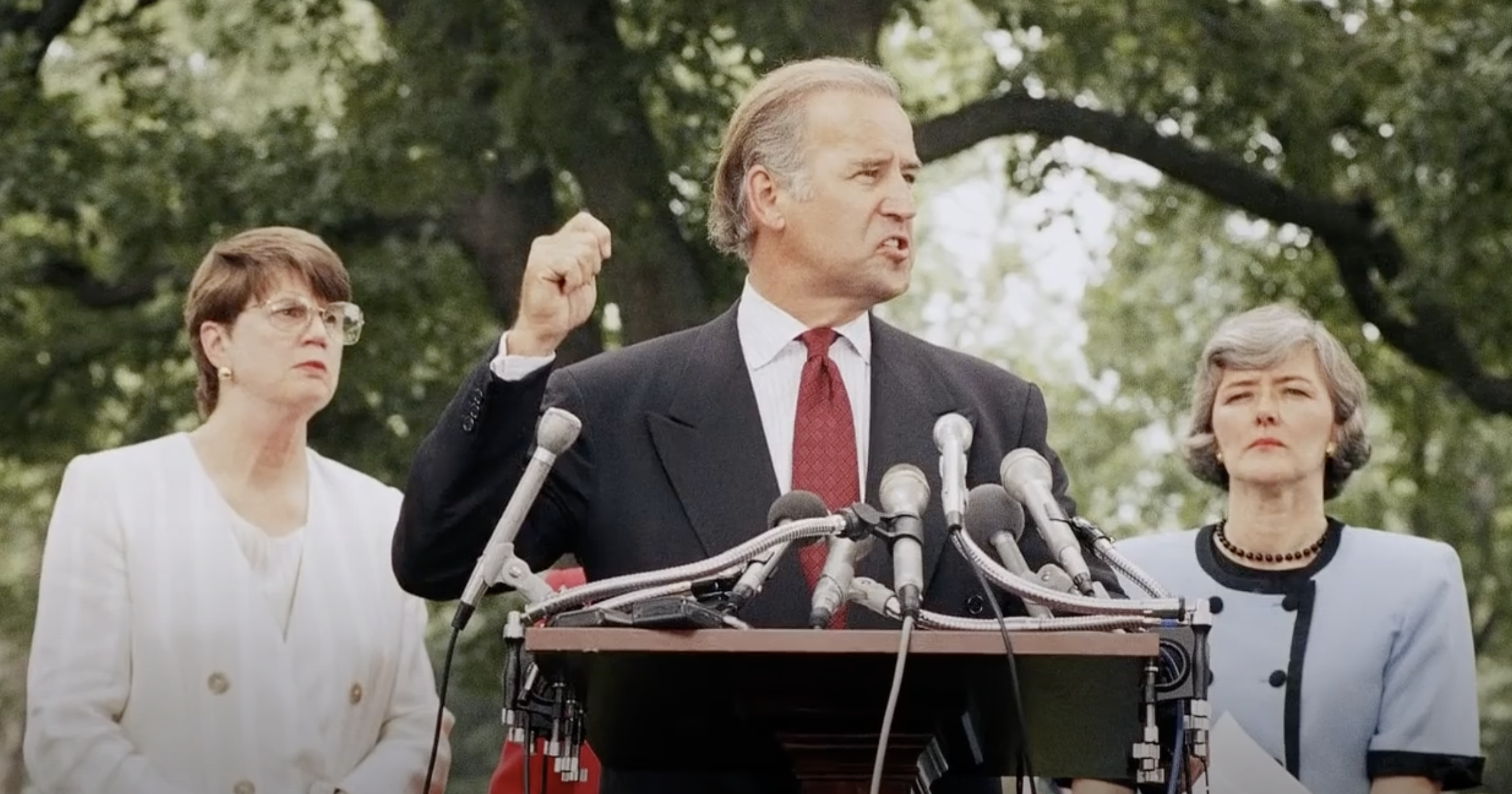

Then Senator Joe Biden talking about the VAWA legislation with cosponsor Rep. Pat Schroeder and Attorney General Janet Reno in the early 1990s. (YouTube)

Yesterday at the White House, President Biden met with survivors, activists, members of his former staff, and former congressional colleagues in an event on the South Lawn (video) celebrating the anniversary of VAWA, saying it was his “proudest legislative achievement.” He also reflected on the bill's passage, its impact over the years, and the need to modernize it to meet the new threats to women online.

As Futures Without Violence founder and president Ester Soler writes in Ms. Magazine, “VAWA’s passage was truly a turning point for our country. This transformative, imperfect but ever-improving law was well worth the years-long effort to get a recalcitrant Congress to pass it.”

A turning point for sure, but we are far from realizing a Future without Violence towards women in this country and around the world. For me, this issue is personal and a priority. When V (formerly Eve) Ensler launched VDAY, a movement to end violence against women everywhere, I signed on as one of her early board members and have considered the work we get to do, offering guidance, funding and support to anti-violence groups in the US and 150 plus other countries, a privilege and a priority!

Our work recognizes the violence that is so misnamed — often referred to as ‘domestic’ or ‘intimate’ — as it is more accurate to describe any act of violence against any woman as an outcome of misogynistic beliefs that women are less equal and until this bill in the US, were also less protected by law.

V and I at the City of Joy in Bukavu, Congo. Since opening its doors in 2011, nearly 2,000 women have graduated from the City of Joy, a community that heals, nurtures, teaches, and inspires survivors of the horrific sexual violence in Eastern Congo to become the leaders needed to make the transformational changes in their villages and country.

Even in the debates in Congress about the bill, as Esta describes: “We had to listen to lawmakers dismiss brutal murders as ‘lovers’ quarrels that got out of hand.’ Some expected us to laugh when they accused us of ‘trying to take the fun out of marriage.’ Many insisted domestic and sexual violence were private matters best handled by families. Never mind the health and economic costs, the dangerous law enforcement engagements, or the trauma that for many lasted a lifetime.”

The consensus among Washington powerbrokers — mirroring public sentiment at the time — was that issues of domestic violence and sexual assault didn’t belong in the public domain.

That has changed. Policymakers and Americans more broadly now recognize family violence as a societal problem, worthy of public attention and investment. And the Violence Against Women Act helped make that happen.

VAWA shows that progress is possible. Between 1993 and 2022, “annual domestic violence rates decreased by 67% and the rate of rapes and sexual assaults dropped by 56%,” reports Newsweek.

As Soler notes in Ms., violence against women may be out of the shadows, but it remains a key issue for American voters in the upcoming election: “On a long list of issues in the newly released YWomenVote survey, women identified domestic and sexual violence as the third most important one facing U.S. women collectively.”

We have made progress, yes, but the work goes on. At Ms., Soler outlines four ways in which VAWA could be improved, including:

Keep looking to improve the law. VAWA provided funds for urgently needed services; improved legal responses; brought health care providers, schools and other institutions into the work; introduced training for judges and law enforcement; launched the National Domestic Violence Hotline; and more. But it wasn’t enough, and we worked continuously to improve and expand the law, making changes to ensure fewer people would be caught up in the criminal justice system, expand it to more communities, provide economic support to survivors, promote prevention, and address the needs of children and youth growing up in homes with violence. We improved VAWA each time it was reauthorized.

Fight for what matters most. Trade-offs are never easy, but we can’t waver on the measures that hold the most promise to stop the violence. We need to fully close the boyfriend loophole so no abusive partner—whether married or not—can access guns; close the stalking loophole so those with convictions or restraining orders for stalking cannot access guns; expand services to cover everyone; allow VAWA funds to support intervention programs focused on abusive partners; address teen dating abuse more fully; and invest more resources to stop child sexual abuse.

Focus more on prevention and healing. We need a greater focus on prevention and culture change and to engage more on high school and college campuses, so everyone learns at an early age that all violence is unacceptable. And for when it does occur, we need more services for traumatized children and adult survivors, including more direct economic support. We need more culturally specific services for communities of color and more support for rural communities. We need to end the backlog in processing rape kits so timely justice is possible for survivors.

Keep up with the times. New technologies and new circumstances (like COVID-19) pose new challenges, and the public policy response has often been inadequate or slow. As a country, we’ve done a poor job of addressing the online abuse, stalking and harassment that are so common, the human trafficking that is present in too many communities, and the growing isolation of young men that often feeds violence and hate. We need to be more nimble and aggressive in meeting emerging challenges because they won’t solve themselves.

Read more at Ms. Magazine and learn more about VDAY's and One Billion Rising's movement work at the VDAY website.

Violence against women is reported more often now, but the numbers of women assaulted and killed keep increasing. Until every woman in the world is free of violence or the threat of violence, none of us is truly free.

With gratitude for those who fought the battles to get this law and with encouragement for us all to remember that the fight to end violence against women is not over…

Onward!

- Pat